community-based conservation efforts of the species by project partnering agencies and other NGOs within south-west Madagascar

Ryan C.J. Walker

Nautilus Ecology, 1 Pond Lane, Greetham, Rutland, LE15 7NW, UK. Department of Life Sciences, The Open University, Faculty of Science, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK.

Email: ryan{at}nautilusecology.org

Introduction

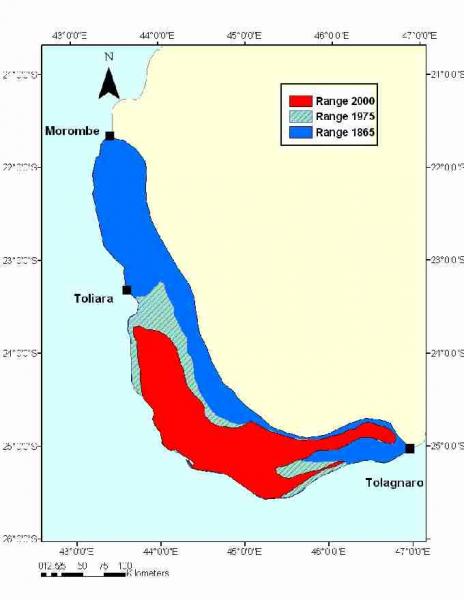

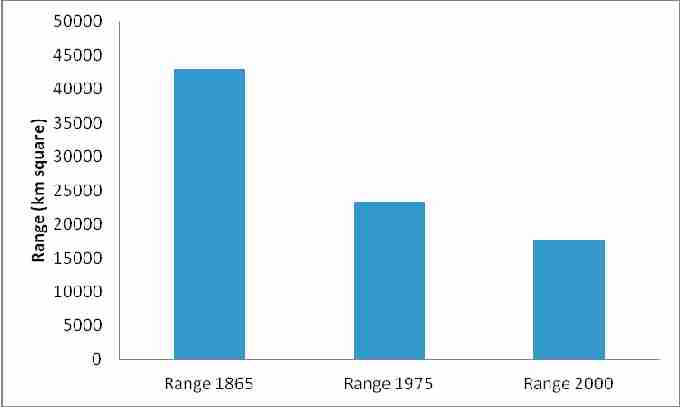

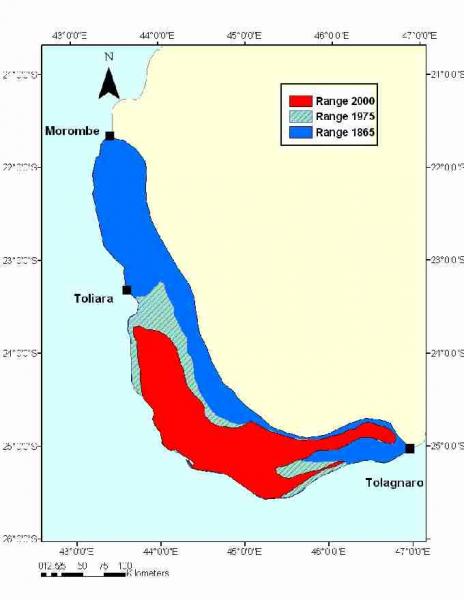

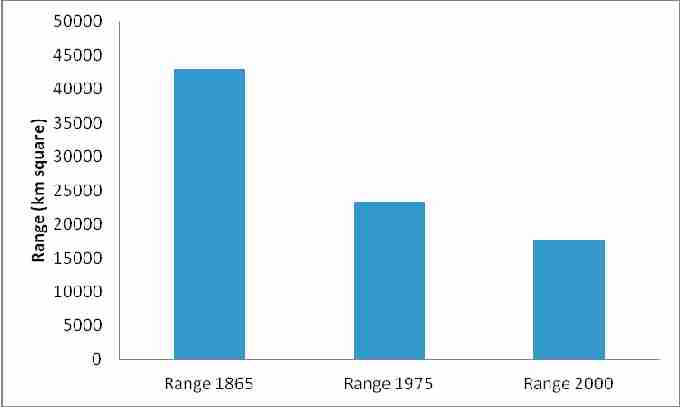

The Madagascar radiated tortoise (Astrochelys radiata) (Fig. 1) is thought to be suffering one of the most rapid declines of any species of tortoise globally. Despite the species’ legally protected status within Madagascar and its Convention for the Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) Appendix I status, banning all international trade in the animal (Pedrono, 2008), it is thought that the species could be extinct in the wild in as little as 20 years (Hudson & Horne, 2010). This decline is evident when one considers that the suspected range of the species was reduced by 20.9% between 1975 and 2000 (Fig. 2; O’Brian et al., 2003), with anecdotal evidence suggesting that in recent years this rate of decline has increased (Hudson & Horne, 2010). This species is endemic to the dry coastal forests of south-west Madagascar, globally one of the most unique ecosystems, with about 90% of the floral species and significant numbers of other reptile species occurring in these forests being endemic to this region (Seddon et al., 2000; Fenn, 2003). However, this region is also the most impoverished and marginalized within Madagascar, which in turn is one of the economically poorest nations in the world (WWF, 2010). As a result, poverty has been one of the major drivers forcing the rapid decline of this iconic species (Fig. 2), due to poaching for both the bush meat and pet trade (Pedrono, 2008; Castellano et al., 2010) and pressures from habitat destruction and alteration (Pedrono, 2008; WWF, 2010) brought about by subsistence agricultural practices (Seddon et al., 2000).

Fig. 1. The radiated tortoise displays characteristic cream or yellow stripes radiating out from the centre of its scutes. The species attains a length of up to approximately 40cm straight carapace length. Photos: (a) R.C.J. Walker (b) B.D. Horne.

Fig. 2. (a) Geographic range of the radiated tortoise. Geographic range of 1865 was inferred from subfossil specimens and 19th century shipping records of tortoise exports (Vinson, 1865; Nussbaum & Raxworthy, 2000); tortoise range in 1975 was established by presence/absence observations (Juvik, 1975; Lewis, 1995). The range in 2000 was estimated from tortoise abundance at 14 sites in southern Madagascar from anecdotal information reported by O’Brien et al. (2003). Fig. 2. (b) Graphical representation of suspected declining range.

This report documents the major conservation issues currently facing the species; in addition to this, some of the BCG funded research currently being undertaken in an attempt to quantify these threats is discussed. Finally, it is reported how these data and other work are being integrated into community-based conservation efforts of the species by project partnering agencies and other NGOs within south-west Madagascar.

Conservation threats

Poaching to support the bush meat trade

O’Brien et al. (2003) and WWF (2010) have calculated that between 46,500 and 60,000 radiated tortoises are illegally harvested annually for bush meat and the pet trade, with O’Brien et al. (2003) stating that their figure could even be just an unquantifiable portion of the total annual harvest. For cultural reasons tortoises are rarely consumed by human populations within the current range of the species (O’Brien et al., 2003; Pedrono, 2008); however, demand is high for tortoise meat within the towns of Toliara and Tolagnaro (Fig. 2a) which exist on the peripheries of the species’ current range (O’Brien et al., 2003; WWF, 2010). Fearing overexploitation, legislation to protect the tortoise under Malagasy law was introduced in 1961 (O’Brien et al., 2003), but in reality this has done little to stem the flow of poached tortoises collected by gangs to support the bush meat trade within these two and other larger towns within Madagascar (WWF, 2010; Castellano et al., 2010).

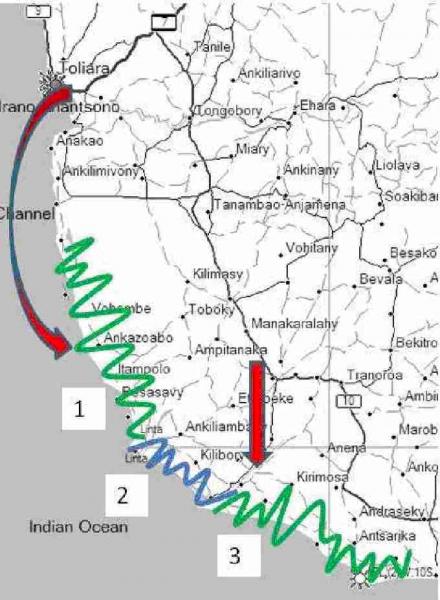

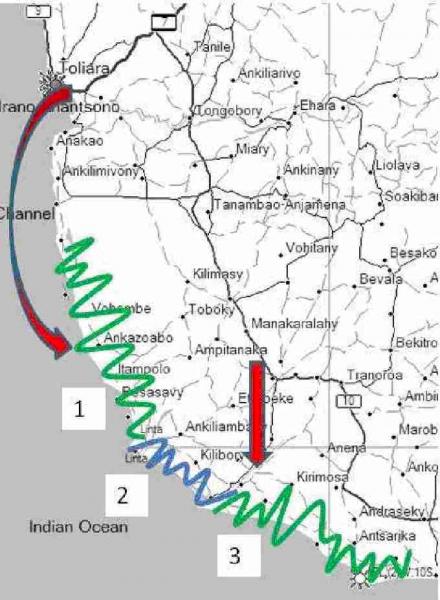

Recent field work by the author and colleagues (Walker, 2010; Castellano et al. 2010; WWF, 2010) has revealed that currently collection hotspots exist within the area between the Linta and Menarandra Rivers and also the Itampolo region. These areas appear to be suffering from moderate to high levels of poaching (Fig. 3). Currently the unpublished results of this preliminary survey reveal numbers of between 1 and 47 slaughtered tortoise carcasses per 1km of transect, mostly within the region between the two rivers (Walker, unpublished data; Fig. 3b; Fig. 4). Local communities also report that armed gangs travel by sea from Toliara to the Itampolo region to collect tortoises. The second trade route is fed by the reasonably serviceable road from Ampanihy to the Linta/Menarandra coastal region (Fig. 3a). The fact that poaching gangs are now arming themselves and intimidating local communities suggests that the tortoise meat trade is considered locally a relatively high value commodity.

Fig. 3. (a) Zone 1 and 3 marked in green represent the regions which support moderate populations of radiated tortoises, while zone 2 in blue shows areas where tortoises were recorded in low numbers. The red arrows represent the trade routes of poachers from Toliara (north) and Ampanihy (north east).

Fig. 3. (b) A visual representation of the number of poached radiated tortoise carcasses encountered upon each 1km transect undertaken throughout area of the species range during February 2010. Circles represent from 1 to 47 poached tortoise carapaces found across 11 1km transects (Walker, unpublished data).

Fig. 4. (a) Radiated tortoise carcasses discarded where they were collected and slaughtered within the forests south of Androka. The tortoise meat has been taken by armed poachers to sell in the large towns of south-west Madagascar.

Fig. 4. (b) A discarded radiated tortoise carapace found at the side of the road, probably slaughtered and eaten opportunistically by the driver of a passing vehicle.

Photos: R.C.J. Walker.

Due to the remote nature of the region and the poor quality of the roads, supply vehicles can often spend days on the road travelling between the few remote towns within the region. As a result passing drivers stop and collect tortoises to eat in a more opportunistic fashion (Walker, 2010), contributing to further declines in the population.

Poaching to support the pet trade

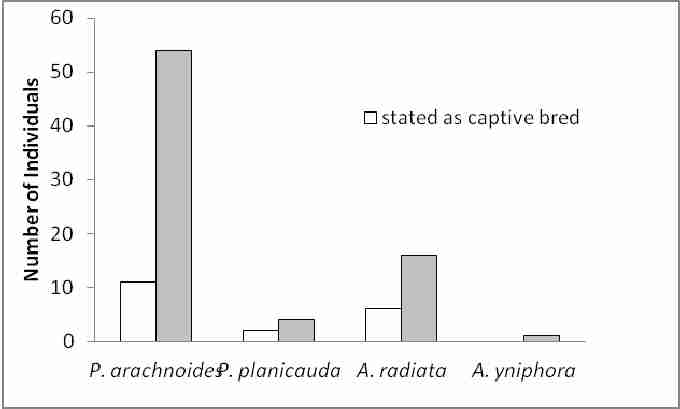

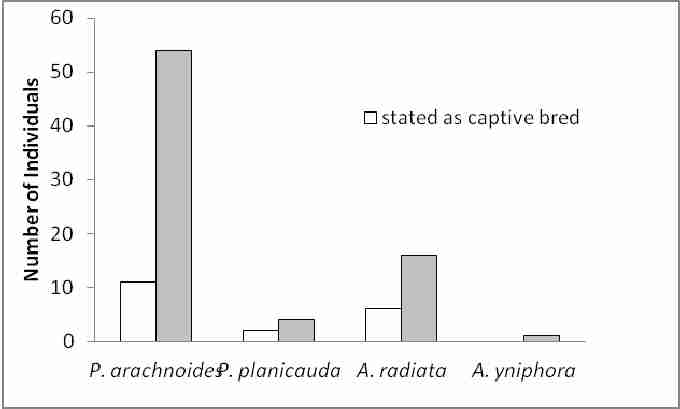

Currently, a portion of the tortoises harvested annually enter the pet trade both internationally and locally (Pedrono, 2008). On account of the species’ attractive carapace patterning radiated tortoises have consistently been one of the most widely traded species of tortoise within the pet markets of south-east Asia in recent years (Nijman & Shepherd, 2007a; 2007b). Despite the species’ CITES Appendix I status, the Internet based trade in the species is rife (Walker, unpublished data). Currently specimens with superior shell patterning sell for up to US$ 28,000 in Japan (Walker, unpublished data). The results of an internet trade monitoring exercise undertaken during September 2009 revealed that more than 50% of the animals offered for sale were advertised without any documentation to prove that they were captive bred (Fig. 5; Walker, unpublished data).

Fig. 5. Results of an Internet based trade monitoring exercise undertaken during September 2009 by the author, documenting the number of Madagascar’s four endemic, Critically Endangered tortoise species offered for sale (Pyxis arachnoides, P. planicauda, Astrochelys radiata and A. yniphora). The graph shows the total number of animals from each species offered for sale openly advertised as captive bred versus the total number of animals which are not stated as captive bred.

Poaching to support international trade is thought to be on the increase on account of current political instability within the country as a result of a government coup in January 2009. The current ineffective government structure within the country and subsequent poor law enforcement have meant that Madagascar has become an easy target for gangs of international wildlife smugglers keen to exploit the current situation. Also, the newly opened direct flight route between Antananarivo and Bangkok, a hotbed for the illegal wildlife trade which supplies the growing demand for exotic species within this part of Asia (Nijman & Shepherd, 2007a; 2007b), could be increasing the problem. During July and August 2010, two consignments of reptiles containing over 300 radiated tortoises were intercepted by customs officials in south-east Asian airports (BBC, 2010).

Radiated tortoises are often kept as pets domestically among the residents of the capital, Antananarivo, and other larger cities within Madagascar (Walker, pers. obs.). The species is also commonly kept within poultry enclosures by people in the south-west and other regions of the country, as the tortoises are thought to ward off parasite infestations amongst domestic chickens (Pedrono, 2008).

Habitat destruction

Harper et al. (2007) reports that the southern spiny forests of Madagascar are one of the country’s most threatened ecosystems, with forest loss calculated at 1.2% per year. Subsistence agricultural practices are having the greatest detriment to the structure of the native vegetation, either through direct clearance for crop production or grazing by goats and cattle (Fig. 6; Seddon et al., 2000; Pedrono, 2008). Unfortunately, in some instances land use pressure has forced livestock herders into protected areas and national parks within the region (Fig. 6a; Seddon et al., 2000), which currently support some of the last remaining good populations of tortoises (Hudson & Horne, 2010).

Fig. 6. (a) Cattle and goat herding in Cap Sainte Marie Special Reserve, one of the last remaining strongholds of the radiated tortoise.

Fig. 6. (b) Land clearance for timber harvesting within the spiny forests of south west Madagascar. Photos: (a) B.D. Horne (b) R.C.J. Walker.

The subsistence production of charcoal within south-west Madagascar is also a major cause of habitat loss (Seddon et al., 2000). The communities living within this region rely on charcoal production for either their subsistence economy or for cooking. The production of charcoal under the primitive conditions available to the charcoal cutters in this region can have a production efficacy of as low as 10-15% (WWF, pers. comm.), resulting in large areas of forest being felled for relatively little return in terms of production.

Invasive species

Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia spp.) (Fig. 7a) was introduced to the region from South America in the 1800s (Rafeliarisoa et al., 2010), probably as a food source for both humans and livestock (O’Brien et al., 2003; WWF, 2010). Due to the cactus’s high moisture content, calorific value and different nutrient content, in comparison to the drought tolerant native vegetation, this invasive species has probably allowed for even greater numbers of grazing stock to be sustained within the region, thus perpetuating the over-grazing problem. Also, the nomadic nature of the grazing practices within the region has allowed for seed dispersal in the droppings of grazing stock to be spread over a greater area than would normally occur in a more settled grazing regime (Walker, pers. obs.).

Fig. 7. (a) The invasive Opuntia spp. cactus now commonplace throughout much of south-west Madagascar.

However, possibly the greatest impact these invasive species are having is the direct impact on the diet and subsequent physiology of the radiated tortoises. This species of tortoise has evolved in an environment wherein the food source is low in moisture and nutrient content and the animal has adapted physiologically accordingly. This newly acquired artificial diet probably contributes to the carapace pyramiding evident in some of the tortoises within areas of high prickly pear abundance (Fig. 7b). Indeed, many of the tortoises displaying these shell deformities have characteristic red staining around their mouth parts indicating that the prickly pear fruits make up a portion of their diet (Fig. 7b). These deformities are often a result of protein excess and low calcium:phosphorus ratios (Jackson et al., 1976). This condition can also result in skeletal deformities and kidney failure (Gerlach, 2004).

Fig. 7. (b) A radiated tortoise displaying the characteristic shell deformities associated with inappropriate diet and stained mouth parts as a result of feeding on Opuntia spp. fruit.

Photos: (a) B.D. Horne (b) R.C.J. Walker.

Conservation action

If the long term survival of wild populations of radiated tortoises is going to be achieved, then a well coordinated and well managed action plan needs to be implemented on account of the wide ranging acute threats facing this species.

WWF have made the radiated tortoise one of their focal species as part of their Southern Spiny Forest Ecoregion Program (WWF, 2010). WWF have been making headway into tackling the complicated issues associated with tortoise poaching within the region through collaborations between Madagascar National Parks (MNP) and the gendarmes (WWF, 2010). Awareness-raising into the effects of the poaching problem has been undertaken by WWF, but unfortunately lack of continuous funding has often hampered this exercise. However, these actions have gone some way to increasing the incidents of tortoise seizures (WWF, 2010). The enforcement actions have often been accompanied by mass awareness campaigns, such as radio shows, advertisements in national newspapers or theatrical items. The rural radio network covering the entire ecoregion initiated by WWF, The Andrew Lee’s Trust and the European Union and theatrical groups formed by local communities are instrumental in these campaigns (WWF, 2010). Between 2001 and 2010 7,855 live tortoises and more than 4.8 tons of meat were confiscated (WWF, 2010); however, this only represents about 2% of the estimated number of tortoises poached within the region each year.

Since 2008 the Southern Madagascar Tortoise Conservation Project, partly funded by the BCG, has been in operation. This project has undertaken and continues to undertake detailed surveying of the spatial distribution of the remaining populations of tortoises. The lack of knowledge of the distribution of the last remaining fragmented populations of this species in this remote region of the country is currently hampering the conservation effort. The results of this work are being used by WWF to identify areas in need of priority conservation action on account of either their high numbers of tortoises or the imminent threat of poaching to these populations.

Other notable projects currently in progress in the region include the work undertaken by The Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership. This group is operated by the Center for Conservation Genetics at Omaha Zoo in Nebraska, and has since 2000 been engaged in the Radiated Tortoise Project (RTP), a community based conservation initiative. This project involves working closely with local communities within the heart of the species’ current range to bring livelihood solutions which address both the environmental and anthropogenic threats to radiated tortoises (Rafeliarisoa et al., 2010). The RTP is addressing the drivers associated with the slash and burn agriculture and charcoal production, through developing a simple fuel briquette easily produced from the invasive Opuntia cactus, cattle dung and sawdust, using a grinder produced from old lawn mower parts and a solar desiccator (Rafeliarisoa et al., 2010). This utilization of a pest species is alleviating the need for charcoal production, plus it is removing an invasive plant which is having a detrimental effect on the tortoises’ health. The project also has a scientific element, whereby researchers are studying the effects on the genetic structure of tortoises in areas of intact habitat versus areas of degraded habitat. An environmental education programme has also been developed and implemented in local schools (Rafeliarisoa et al., 2010).

The conservation issues facing the radiated tortoise were the focus of attention at the recent 8th Annual Symposium on the Conservation and Biology of Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles (Florida, August 2010) – a joint meeting of the Turtle Survival Alliance and IUCN Tortoise and Fresh Water Specialist Group. It was proposed that a Madagascar Tortoise Conservation Partnership between NGOs and institutions such as WWF, The Turtle Survival Alliance, Conservation International, the IUCN Specialist Group and the Wildlife Conservation Society, be formed to combat some of the conservation issues facing the four endemic and Critically Endangered species of tortoise in Madagascar.

The issues facing the radiated tortoise are complicated and wide ranging. However, regional and nationwide projects such as the work being implemented by WWF and the community based work implemented by the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership and other NGOs are making some progress. These projects needed to be maintained and in most cases developed and expanded to other regions within the tortoises’ current range, so that a combination of community based environmental education, poverty alleviation and law enforcement can help to protect the radiated tortoise and prevent what is currently predicted to be the imminent extinction of this species in the wild.

Acknowledgements

In addition to BCG funding, some of the field work undertaken by the author and described in this paper was also financially supported by conservation grants from the EAZA/Shellshock Turtle Conservation Fund, the Turtle Survival Alliance, The Mohammed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, the Royal Geographical Society and The Leicester Tortoise Society. Logistical support and help with recent field work in south-west Madagascar was provided by Eddie Louis and the Henry Doorly Zoo Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership Project, Brian Horne, Tsilavo Rafeliarisoa, Richard Razafimanatsoa, Juln Bruchard, Al Harris and project partners Blue Ventures Conservation. I am grateful to Brian Horne for use of some of his photographic material. Thanks are extended to the coastal forest communities of south-west Madagascar for granting access to community owned land.

References

BBC (2010) Smuggled rare Madagascar tortoises seized in Malaysia.

www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-10674741 [accessed 16-02-13]

Castellano, C.M., Doody, J.S., Rakotondrainy, R., Ronto, W., Mahamsina, T., Duchene, J. & Randria, Z. (2010). Slaughtered: Scenes from a radiated tortoise camp. Turtle Survival Magazine August 2010, pp. 67-68.

Fenn, M. (2003). The spiny forest ecoregion. In: The natural history of Madagascar (eds. S.M. Goodman & J. P. Benstead), University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, USA, pp. 1525-1530.

Gerlach, J. (2004). Effects of diet on the systematic utility of the tortoise carapace. African Journal of Herpetology 53: 77-85.

Harper, G., Steininger, M., Tucker, C., Juhn, D. & Hawkins, F. (2007). Fifty years of deforestation and forest fragmentation in Madagascar. Environmental Conservation 34: 325-333.

Hudson, R. & Horne, B.D. (2010). Troubled times for radiated tortoises. Turtle Survival Magazine August 2010, pp. 64-66.

Jackson, C.G., Trotter, J.A., Trotter, T.H. & Trotter, M.W. (1976). Accelerated growth rates and early maturity in Gopherus agassizi. Herpetologica 32: 139-145.

Juvik, J.O. (1975). The radiated tortoise of Madagascar. Oryx 13: 145-148.

Lewis, R. (1995). Status of the Radiated Tortoise (Geochelone radiata). Unpublished Report, WWF, Madagascar.

Nijman, V. & Shepherd, C.R. (2007a). Trade in non-native, CITES-listed, wildlife in Asia, as exemplified by the trade in freshwater turtles and tortoises (Chelonidae) in Thailand. Contributions to Zoology 76(3): 207-212.

Nijman, V. & Shepherd, C.R. (2007b). An overview of the regulation of the freshwater turtle and tortoise pet trade in Jakarta, Indonesia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia.

Nussbaum, R.A. & Raxworthy, C.J. (2000). Commentary on conservation of ‘Sokatra’, the radiated tortoise (Geochelone radiata) of Madagascar. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation 2(1): 6-14.

O’Brien, S., Emahalala, E.R., Beard, V., Rakotondrainy, R.M., Reid, A., Raharisoa, V. & Coulson, T. (2003). Decline of the Madagascar radiated tortoise (Geochelone radiata) due to overexploitation. Oryx 37: 338-343

Pedrono, M. (2008). The Tortoises and Turtles of Madagascar. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia.

Rafeliarisoa, T.H., Shore, G.D., McGuire, S.M. & Louis Jr, E.E. (2010). Innovative solutions to conservation challenges for the radiated tortoise (Astrochelys radiata) project at Lavavolo Classified Forest, Madagascar. Turtle Survival Magazine August 2010, pp. 64-66.

Seddon, N., Tobias, J., Young, J.W., Ramanampamonjy, J.R., Butchart, S. & Randrianizahana, H. (2000). Conservation issues and priorities in the Mikea Forest of south-west Madagascar. Oryx 34: 287-304.

Vinson, A. (1865). Voyage à Madagascar. A La Librairie Encyclopedique de Roret, Paris, France.

Walker, R.C.J. (2010). The south west Madagascar tortoise survey project: End of phase 2 preliminary report to donors and supporters. Unpublished Report by Nautilus Ecology, p. 23.

WWF (2010). Programme d’actions de WWF sur les tortues terrestres endémiques du sud-ouest de Madagascar: Astrochelys radiata et Pyxis arachnoides 2010-2015. WWF Madagascar, p. 61.

Testudo Volume Seven Number Three.

Top