J.R. Downie¹, Heather Muir¹, Madelein Dinwoodie¹, Laura McKinnon¹, Lyndsey Dodds¹ and Matt Cascarina².

¹Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology

Graham Kerr Building

University of Glasgow

Glasgow G12 8QQ

email: J.R.Downie(at)bio.gla.ac.uk

²RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus

Introduction

It is well known that all seven species of marine turtles are threatened with extinction. The World Conservation Union (IUCN) classes them as between vulnerable and critically endangered, and all species are on Appendix 1 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of wild fauna and flora (CITES). Turtles face ‘natural’ threats from predators and diseases, but their long term survival (turtles have inhabited the world’s oceans for over 150 million years) suggests that their recent plight is related to changes in the environment brought about by human activities.

In the Mediterranean, two species of marine turtle nest (the loggerhead, Caretta caretta and the green, Chelonia mydas) while a third, the leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) is an occasional visitor. Venizelos (2002) has outlined the threats faced by turtles in the Mediterranean: beach developments and uses incompatible with successful nesting; pollution; by-catch of adults. Rees et al. (2002) have reported on the turtle protection work carried out on the west of Greece at Kyprassia Bay by Archelon, the Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece: this project employs a large team of volunteers through the nesting season in nest monitoring and management, plus a public education programme. Similar work is carried out in Northern Cyprus, principally at Alagadi by student teams organised through the Marine Turtle Group originally from Glasgow, but now at the University of Swansea (Broderick and Godley, 1996). In addition, this project carries out research on turtle biology, particularly aspects related to conservation, such as the effects of nest temperature on hatchling sex ratio (marine turtles all use Temperature Sex Determination, with a middle third of incubation mean temperature of 29.5°C resulting in a 50:50 sex ratio, but temperatures much above this producing all females, and below – all males). At RAF Akrotiri in southern Cyprus, a team of volunteers from the base has been involved in turtle nest monitoring and protection since 1991. For the last 5 years, much of the work has been done by students from the University of Glasgow, latterly as University of Glasgow expeditions, supported by the University’s Exploration Society. These Turtlewatch teams have worked closely with RAF personnel, especially Matt Cascarina and previously Wayne Eves, Turtlewatch co-ordinators. The presence of the students has allowed intensive monitoring from early June (as soon as examinations are over, fortunately coinciding with the start of the nesting season) to late September (by which most nests have hatched). The number of students involved has averaged 15 per season with some being in Cyprus throughout the project but most working a 6-8 week shift. The students raise the funds to support the project through small grant applications (to organisations like the British Chelonia Group), their own fundraising activities (raffles, stunts, street-collections) and personal contributions. The RAF helps with accommodation and canteen catering. It is worth emphasising the dedication required of the students involved: they have to spend considerable time during the University term in raising funds, then much of the summer on the project when they could be earning money to clear the debt modern students accumulate. There is the compensation, however, that marine turtles do tend to nest in attractive places!

Study Site

Turtles nest on four beaches on the western side of the Akrotiri Peninsula (Fig.1), close to the RAF base. The beaches are 575, 400, 75 and 300 metres in length respectively and are backed by rocky cliffs up to 20 metres high, which provide morning shade. The beaches lie within the UK’s Sovereign Base Area and are therefore under British jurisdiction. This has resulted in a very low level of development and a low degree of human impact, though extensive fishing occurs offshore. Signs have been erected, both in English and in Greek, forbidding dog owners to take their dogs on to the beaches, and forbidding vehicular access.

Turtle Monitoring

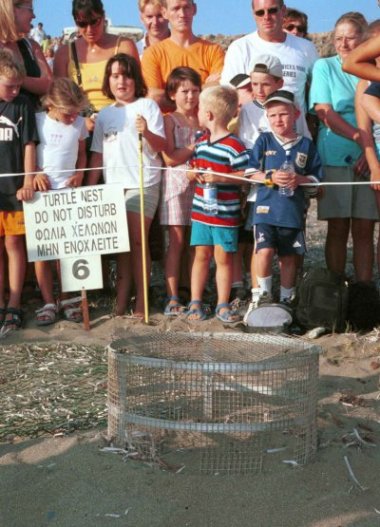

The beaches are monitored nightly during the nesting season (new nests peter out about mid-August): the turtle team splits into two groups, each taking half of the beaches and patrolling at hourly intervals, without the aid of lights. When a fresh turtle track is located, the team follows it till the turtle is found, or the track returns to the sea with no nest made (false crawl). Once the turtle is found, nesting is watched till completion and once the turtle has returned to the sea, the nest site is covered with an anti-predator wire mesh cage, buried in the sand to a depth of 10cm. The cage mainly protects against dogs and foxes. A sign with the nest number and "Turtle Nest: Do not disturb"" in both Greek and English is placed just behind each nest. Turtle species is determined either from the shape of the tracks in the sand, or by observing the actual turtles. Later in the season, from late July onwards, hatching is also monitored: two days after the first hatchlings have emerged, the nest is excavated to release any hatchlings that have been trapped in the sand. At this time, data are collected such as nest depth and number of eggs (hatched and unhatched) to add to other parameters such as nest position. The basic data from the nest monitoring are shown in Table 1. As elsewhere on Cyprus, loggerheads nest in larger numbers than greens. Clutch sizes and incubation durations are broadly comparable year to year. Nest depths are more variable than expected, but this may reflect differences in technique: it is difficult to ensure accurate and comparable measurements of this parameter.

| Turtle | Year | Number | Mean incubation duration (days) | Mean nest depth (cm) | Mean clutch size | Mean hatching success (%) |

|---|

| Loggerheads | 1998 | 22 | 54.8 | - | - | 63.8 |

| 1999 | 10 | 59.0 | - | 67.0 | 80.6 |

| 2000 | 9 | 51.7 | 44.8 | 81.6 | 80.2 |

| 2001 | 21 | 49.5 | 50.5 | 88.0 | 67.3 |

| 2002 | 23 | 54.4 | 53.5 | 87.1 | 63.4 |

| Greens | 1998 | 6 | 52.8 | - | - | 89.9 |

| 1999 | 7 | 63.0 | - | 96.0 | 82.8 |

| 2000 | 7 | 51.9 | 66.8 | 100.6 | 94.0 |

| 2001 | 3 | 51.0 | 87.5 | 108.5 | 70.9 |

| 2002 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

Table 1. Nesting data for the Akrotiri Peninsula, 1998-2002.

In addition to basic nest monitoring, nest relocation is carried out wherever a nest is laid so close to the sea that it is in danger of being waterlogged by the tide. In 2002, two loggerhead nests were relocated to sites further up the beach. Both nests hatched with 90% success, showing that the relocation was a highly effective procedure.

Public Education

The Turtlewatch project recognises the importance of public education about the plight of marine turtles. Once most hatchlings have emerged from a nest, the nest is excavated to release any trapped hatchlings and to collect basic data. These excavations are carried out in public, with up to 100 people attending including RAF personnel and local Cypriots, and preceded by a short presentation on what the project aims to do and why. The project also runs a shop and information centre at the base.

Photos by Cpl Gareth Davies. RAF Akrotiri

Research

With the approval of the Turtlewatch project co-ordinator, Glasgow students have carried out a number of non-invasive research projects on the nesting biology of marine turtles. These have included studies on the relationships between sand quality and nesting success, measurements of intranest temperature and metabolic heating within nests using continuous temperature dataloggers, and observations on hatchling orientation and mobility. Some of this work has generated results interesting enough that papers are likely to be published in scientific journals.

Conclusion

The number of turtles nesting on the Akrotiri Peninsula is relatively small (our four year average is 19 loggerheads and 4 greens on 1.4km of beach compared to over 500 loggerhead nests on 9.5km at Kyparissia Bay in the Western Peloponnese of Greece, as reported by Rees et al, 2002). However, given the generally downwards trends worldwide, any successful nesting beach is worth protecting, especially those that are less in danger of tourist development, as is the case for Akrotiri, because of the RAF base. Too often, conservation effort is aimed solely at the cases of most extreme threat, neglecting places/species where a lesser degree of care had a good chance of success (Possingham, et al. 2002). In the case of marine turtles, high nest site fidelity and long adult life-span mean that any successful nesting beach is well worth looking after.

A considerable benefit of the Turtlewatch project is that it is accumulating a long-term data set on nesting numbers and success rates. It is generally agreed (Bjorndal et al., 1999) that year-to-year variation in turtle nesting numbers makes it impossible to discern nest trends without long-term data.

However, nest protection and data collection are very time-consuming. In the Mediterranean, the combined nesting and hatching season stretches from late May to early October, almost 20 weeks. Beach patrolling at night is hard work and safety requirements mean that quite large numbers of people are needed. Rarely is there any payment, so turtle protection schemes round the world rely on volunteers, mostly young people. Although senior school pupils can help with such work, the requirement for accompaniment by school staff severely limits what can be achieved. Poland et al. (1996) reported on the valuable work done by a school group on Zakynthos: they helped with turtle monitoring but concentrated on an awareness survey of tourists: they were on Zakynthos only for two weeks.

University undergraduate expeditions can achieve a great deal more: they can stay longer, and can often have real expertise, especially when the expedition is repeated annually: it is common with Turtlewatch for a student to take part for the first time in first or second year, then return the next year as a group or overall expedition leader. Another considerable benefit from undergraduate expeditions is their capacity for doing genuine research to add to our much needed knowledge of marine turtles.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the students who have taken part in GU Turtlewatch expeditions to date and to Matt Cascarina and all the other Turtlewatch helpers at RAF Akrotiri. Thanks also to all our financial sponsors.

References

Bjorndal, K.A., Wetherall, J.A., Bolten, A.B. and Mortimer, J.A. (1999). Twenty-six years of green turtle nesting at Tortuguero, Costa Rica: an encouraging trend. Conservation Biology 13, 126-134.

Broderick, A.C. & Godley, B.J. (1996). Population and nesting ecology of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, and the loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta, in northern Cyprus. Zoology in the Middle East 13, 27-46.

Poland, R.H.C., Hall, G.B. & Smith, M. (1996). Turtles and tourists: a hands-on experience of conservation for sixth formers from King’s College, Taunton, on the Ionian Island of Zakynthos. Journal of Biological Education 30, 120-128.

Possingham, H.P., Andelman, S.J., Burgman, M.A., Medellin, R.A., Master, L.L. & Keith, D.A. (2002). Limits to the use of threatened species lists. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 17, 503-507

Rees, A., Tzovani, L. & Margaritoulis, D. (2002). Conservation activites for the protection of the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) in Kyparissia Bay, Greece, during 2001. Testudo 5 (4), 45-54.

Venizelos, L. (2002). Mediterranean sea turtles. Testudo 5 (4), 31-36.

Testudo Volume Five Number Five 2003

Top