Julie Jackson1,2, James Lewis1,3, Rachel Graham3 and Brendan Godley1

1Centre for Ecology and Conservation, School of Biosciences, University of Exeter, Cornwall Campus, Treliever Road, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9EZ, UK.

2Current address: Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Arlington, VA, USA. E-mail: jjackson@conservation.org

3 Ocean Giants Program, Wildlife Conservation Society, PO Box 76, Punta Gorda, Belize.

Introduction

As a marine biodiversity hotspot (Roberts et al., 2002) and a ‘Global 200’ conservation priority area (Olson & Dinerstein, 1998), the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (MBRS) is an economically and ecologically important zone for both Belize and the Caribbean region as a whole. The MBRS encompasses essential habitats for a range of endangered and critically endangered marine species. These include several important foraging and breeding grounds for critically endangered hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata), the focal species of this study.

It is widely accepted that after a long pelagic period, juvenile hawksbill turtles of approximately 20-25cm CCL (curved carapace length) inhabit a foraging ground, usually on or near coral reefs (Carr, 1987), where they may reside until migrating to adult nesting grounds which could be hundreds of kilometres away (Bowen et al., 1996; 2007). Developing our understanding of how hawksbills use these different habitats will help conservation planners in the long-term management of marine turtle populations.

Belize has had a long and prolific marine turtle fishery until populations began to decline in the mid 20th century (Smith et al., 1992). Sea turtle eggs, small juveniles and nesting females gained protection in 1977 and there was a ban on all fishing of turtles between June 1 and August 31 each year. Smith et al. (1992) reported that the ban on egg exploitation was widely ignored, turtles were still being taken for their meat, juvenile hawksbills were captured, stuffed and sold as wall decorations, and there was an ongoing demand for tortoiseshell products, largely from US tourists. Though hawksbill turtles received full protection in 1993, there are accounts that exploitation continues to some degree (Meerman, 2005). Though the current level of harvest is unknown, with intense protection and informed management the juvenile hawksbill breeding grounds of Belize could help to repopulate other areas of the Caribbean.

Lighthouse Reef Atoll (LRA), in Belize, is one of four atolls on the MBRS and encompasses the World Heritage sites Blue Hole and Half Moon Caye Natural Monuments. In 2007 the Belize Audubon Society (BAS), managers of Blue Hole and Half Moon Caye Natural Monuments, identified three species of marine turtle – hawksbill, green (Chelonia mydas) and loggerhead (Caretta caretta) – as Conservation Targets for the area. With up to 600 fishers and over 7000 tourists1 using the atoll annually, a comprehensive understanding of the flora and fauna within the atoll is clearly needed to aid with management planning.

In this study, the University of Exeter, in collaboration with The Wildlife Conservation Society, conducted the first acoustic turtle tracking study in the MBRS in May 2009 to develop a better understanding of how juvenile hawksbill turtles use LRA. Prior to this study, to our knowledge, no formal research had been undertaken to assess the juvenile hawksbill turtle population of LRA or their use of the area.

Study site

The turtle tracking study was conducted over the course of 16 days from 30 April to 15 May 2009 along the western forereef of LRA, a coral-rimmed atoll that contains six cayes and two ‘no-take’ marine protected areas. Two areas within LRA were used for the purposes of this study. Study sites were chosen based on local fisher sightings of hawksbill turtles in the area and boat access. Figure 1 shows the study sites along the atoll. Site 1, Central LRA, was located approximately five kilometres NNE (17° 15’ N, 87° 34’ W) off the northern tip of Long Caye along the western forereef. Site 2, Long Caye, was located along the western side of Long Caye along the western forereef (17° 12’ N, 87° 36’ W).

Fig. 1. Study sites at Lighthouse Reef Atoll, Belize: a) ‘Central LRA’ and b) ‘Long Caye’. (Adapted from Google Earth)

Methods

This study relied on the use of active acoustic telemetry to ascertain the movements of juvenile hawksbill turtles on the western, or leeward, side of LRA. Active acoustic telemetry is an important tool used to study marine animals, allowing the continuous or periodic tracking of submerged animals, resulting in high resolution location points. Active acoustic telemetry requires the use of a transmitter (or tag), attached to an animal, and a hydrophone (Fig. 2) and receiver, attached to a mobile vessel. The hydrophone, placed in the water, detects the signal emitted by the transmitter when it is located within range.

Fig. 2. Omnidirectional hydrophone in the water.

Turtles were located and captured with the help of a team of local experienced free-divers who snorkelled along predetermined transects until a turtle was located, at which point an attempt was made to capture the animal (Fig. 3). A total of 11 turtles were sighted during these transects of which 10 were caught, occasionally at depths of about 20m, a clear indication of the skill of the free-diving team. Once a turtle was captured it was brought onto a small skiff, the head was lightly covered with a moist towel to keep it calm while it was measured and a Vemco V16-6H tag (Vemco, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada) was applied to the carapace of the turtle using a paste epoxy (Figs 4-5). All turtles were also tagged in both front flippers with metal Inconel flipper tags (National Band and Tagging Co. 1005-681, Newport, KY, USA) for identification purposes (Fig. 6). Each turtle was measured for the minimum curved carapace length (CCLmin; Bolten, 1999) and weighed to the nearest 0.5kg. After approximately an hour (enough time to allow the epoxy to set) the turtle was returned to the water at the location where it was captured (Figs 7-9).

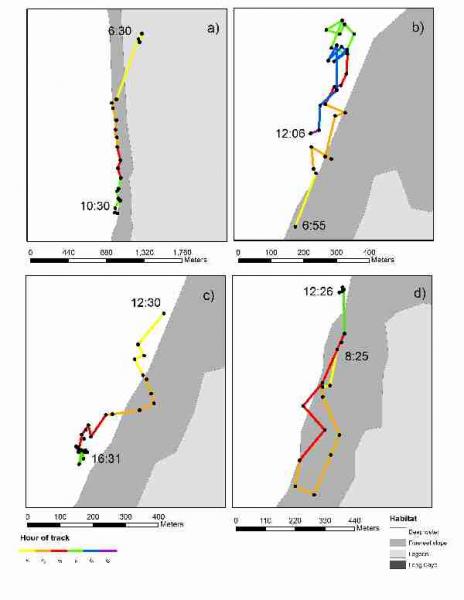

After a 24 hour acclimatization period, the tagged turtles were actively tracked from a boat using a Vemco VR100 general-purpose ultrasonic receiver and VH165 omni-directional and VH110 directional hydrophones (Figs 10-11). An attempt was made to locate each turtle every one or two days. Extended tracks were conducted to record fine-scale movements within the atoll. Location points were obtained approximately every 10 minutes (range 4-40 minutes) and habitat types were noted. These data were then used to calculate home ranges and to observe fine-scale movement.

Fig. 3. Snorkellers on parallel transects searching for turtles.

Fig. 4. Juvenile hawksbill turtle with an acoustic tag, waiting for the putty to set. The turtle has a wet washcloth over its head to help keep it calm.

Fig. 5. Close-up of tag attached to carapace, leaving the transmitting end exposed

Fig. 6. Tag attached to base of flipper.

Fig. 7. Releasing turtle in location where it was found.

Fig. 8. Tagged turtle swimming along bottom. Both the metal flipper tag and the acoustic tags are visible (the second acoustic tag was for a separate study).

Fig. 9. Tagged turtle swimming above Lighthouse Reef Atoll’s forereef.

Figs 10-11. Searching for turtles with the Vemco V100 tracking unit (grey box) and the VH110 hydrophone (in the water).

Results and discussion

Through this study we were able to gain preliminary results on the size of hawksbill turtles inhabiting the study sites (Fig. 12) and their home range. We were also able to investigate habitat preference and behaviour of the turtles. Figure 13 shows examples of the type of extended track data that was collected during the course of this study. Because the survey time was short and sample size low, this research will be combined with future studies to shed light on abundance and behaviour of this potentially important juvenile hawksbill turtle feeding ground.

It is clear, however, that LRA is a foraging ground for juvenile hawksbill turtles and with further study it may be deemed an important one for the region. Though LRA lies approximately 100km from the mainland it is still a popular place in Belize for fishing and diving. An estimated 23 boats associated with tourism utilize LRA (Graham et al., 2005), many visiting the western forereef, mooring directly over the wall or on the adjacent forereef (pers. observation). Given the observed high level of use of the wall and forereef by the turtles and the fact that many dive boats frequent the wall and adjacent forereef there may be potential for disturbance to the turtles from anchoring or from divers. The direct effect this may have on the turtles is unknown, but indirect damage due to habitat destruction may be possible as damage to the coral reef habitat at LRA has been reported (Kramer & Kramer, 2002) and anchoring and diving have caused similar damage to other reefs in the past (e.g. Davis, 1977; Jameson et al., 1999).

This pilot study has indicated that a substantial amount of information can be obtained about a population of juvenile hawksbill turtles in a short period of time using active acoustic telemetry. University of Exeter in partnership with the Wildlife Conservation Society will expand this pilot project in the coming years to gain a better understanding of the home range and movements of juvenile hawksbill turtles at LRA in relation to threats and conservation opportunities. Results from this study, combined with future research, will be published and will provide information beneficial to the management of juvenile hawksbill turtles at LRA and potentially the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef region. Informed management of this and other juvenile hawksbill foraging grounds could prove to be beneficial to breeding populations throughout the Caribbean.

Fig. 12. One of the larger turtles captured.

Fig. 13. Examples of extended tracks conducted during survey (LRA, Belize, May 2009).

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the guidance, hard work and financial support from a number of people and organizations. Thank you to the Fisheries Department of Belize for allowing the work to take place under Wildlife Conservation Society research permit number 011-09. We are grateful to the Wildlife Conservation Society for their logistical and financial support, to the Belize Audubon Society for allowing us to stay at Half Moon Caye and to the British Chelonia Group and Vemco for their financial support. And finally, I cannot express adequate thanks to the expedition team members Dan Castellanos, Daniel Castellanos, Jason Castro, Darren Castellanos, Edlin Leslie and ‘Tiger’ Orrington for their help in catching turtles and captaining boats.

References

Bolten, A.B. (1999). Techniques for measuring sea turtles. In: Eckert, K.L., Bjorndal, K.A., Abreu- Grobois, F.A. & Donnelly, M. (eds). Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles. IUCN/SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group Publication No. 4, 1999.

Bowen, B.W., Grant, W.S., Hillis-Starr, Z., Shaver, D.J., Bjorndal, K.A., Bolten, A.B. & Bass, A.L. (2007). Mixed-stock analysis reveals the migrations of juvenile hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Caribbean Sea. Molecular Ecology 16: 49-60.

Bowen, B.W., Bass, A.L., Garcia-Rodriguez, A., Diez, C.E., van Dam, R., Bolten, A., Bjorndal, K.A., Miyamoto, M.M. & Ferl, R.J. (1996). Origin of hawksbill turtles in a Caribbean feeding area as indicated by genetic markers. Ecological Applications 6: 566-572.

Carr, A. (1987). New perspectives on the pelagic stage of sea turtle development. Conservation Biology 1(2): 103-121.

Davis, G.E. (1977). Anchor damage to a coral reef on the coast of Florida. Conservation Biology 11(1): 29-34.

Graham, R.T., Hickerson, E., Barker, N. & Gall, A. (2005). Rapid Marine Assessment; Half Moon Caye and Blue Hole Natural Monuments, Lighthouse Reef Atoll, Belize. Belize Audubon Society, 66 pp.

Jameson, S.C., Ammar, M.S.A., Saadalla, E., Mostafa, H.M. & Riegl, B. (1999). A coral damage index and its application to diving sites in the Egyptian Red Sea. Coral Reefs 19: 333-339.

Kramer, P.A. & Kramer, P.R. (2002). Ecoregional Conservation Planning for the Mesoamerican Caribbean Reef (ed. M. McField). Washington, D.C., World Wildlife Fund.

Meerman, J. (2005). Compilation of Information on Biodiversity in Belize. Report to Inbio and Forest Department of Belize.

Olson, D.M. & Dinerstein, E. (1998). A representation approach to conserving the Earth’s most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biology 12(3): 502-515.

Roberts, C.M., McClean, C.J., Veron, J.E.N., Hawkins, J.P., Allen, G.R., McAllister, D.E., Mittermeier, C.G., Schueler, F.W., Spalding, M., Wells, F., Vynne, C. & Werner, T.B. (2002). Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295: 1280-1284.

Smith, G.W., Eckert, K.L. & Gibson, J.P. (1992). WIDECAST Sea Turtle Recovery Action Plan for Belize (Karen L. Eckert, ed.). CEP Technical Report No. 18 UNEP Caribbean Environment Programme, Kingston, Jamaica. 86 pp.

Testudo Volume Seven Number Two 2010

Top